The Egba women of Nigeria are keeping the craft of Adire making alive, and in doing so, earn modest forex for Nigeria.

Johnson Bolatito’s Adire fabrics hung across the clothesline, swaying gently in the direction of the morning wind. Moments earlier at her cottage in Itoku area of Abeokuta, Ogun State capital, she had arranged the fabrics carefully across the twine to form a mélange of colours suspended into the firmament like a rainbow.

Ms Bolatito moved gently through a heap of clothes submerged in coloured water, unperturbed by the roaring sounds of an impending downpour. Away from the open verandah of the cottage, a cloud of steam escapes into the skies from a black pot of hot water placed on the edge of a nearby gutter. Beside the pot lie a few plastic buckets, and some metres away stood yet another black pot filled with water.

“We need water to make the coloured patterns come out well,” Ms Bolatito says in her native Egba dialect, her eyes fixated on the clothing materials.

“Making and designing Adire can be very stressful, as you’d see, but the result is always beautiful. Of course, we make good money from it, too.”

Inside the old houses adjacent to the popular Kampala Market in Itoku area of Abeokuta, capital of Ogun State, there are numerous Egba women designing traditional Adire clothing materials.

Bolatito, 46, is one of them. She earns a living from the art of Adire cloth-making. She speaks to PREMIUM TIMES in the company of Jumoke, 38, another entrepreneur at the Itoku cottage.

“This is what I do, from which I feed myself, send my children to school and enjoy life,” says Jumoke, who would not give her second name.

“Many of the people doing this business have done very well for themselves, building houses and all that. Many of those who make the biggest money are those who can invest enough capital into the business.”

Jumoke refers to wealthy suppliers and owners of the big shops at popular Adire markets in Abeokuta, such as the Kampala Market, Panseke Market, Osiele Market, and other major markets in the ancient city.

“Many of those women are directly involved in the processing and designing like we do here,” she says, grinning. “But you may not know until you see them ‘get dirty’ inside coloured water here.”

From the sale of Adire, she has used the proceeds to support her family since her husband lost her job at the height of the Covid-19 crisis.

“Adire making is a good business, and depending on how much patronage we get, the proceeds could run into tens of thousands of naira monthly,” she says.

ian women ‘dyeing’ to boost Nigeria’s forex earnings

The Egba women of Nigeria are keeping the craft of Adire making alive, and in doing so, earn modest forex for Nigeria.

ByOladeinde OlawoyinJuly 9, 2021 9 min read

Johnson Bolatito’s Adire fabrics hung across the clothesline, swaying gently in the direction of the morning wind. Moments earlier at her cottage in Itoku area of Abeokuta, Ogun State capital, she had arranged the fabrics carefully across the twine to form a mélange of colours suspended into the firmament like a rainbow.

Ms Bolatito moved gently through a heap of clothes submerged in coloured water, unperturbed by the roaring sounds of an impending downpour. Away from the open verandah of the cottage, a cloud of steam escapes into the skies from a black pot of hot water placed on the edge of a nearby gutter. Beside the pot lie a few plastic buckets, and some metres away stood yet another black pot filled with water.

“We need water to make the coloured patterns come out well,” Ms Bolatito says in her native Egba dialect, her eyes fixated on the clothing materials.

“Making and designing Adire can be very stressful, as you’d see, but the result is always beautiful. Of course, we make good money from it, too.”

Inside the old houses adjacent to the popular Kampala Market in Itoku area of Abeokuta, capital of Ogun State, there are numerous Egba women designing traditional Adire clothing materials.

Ms Bolatito, 46, is one of them. She earns a living from the art of Adire cloth-making. She speaks to PREMIUM TIMES in the company of Jumoke, 38, another entrepreneur at the Itoku cottage.

“This is what I do, from which I feed myself, send my children to school and enjoy life,” says Jumoke, who would not give her second name.

“Many of the people doing this business have done very well for themselves, building houses and all that. Many of those who make the biggest money are those who can invest enough capital into the business.”

RelatedNews

WHO insists COVID-19 vaccines outweigh risks

Again, FG wades into Kaduna govt., NLC dispute, inaugurates committee

350 persons died in boat mishaps in 2020 – Nigerian Official

Tears as flood wreaks havoc in Taraba

Jumoke refers to wealthy suppliers and owners of the big shops at popular Adire markets in Abeokuta, such as the Kampala Market, Panseke Market, Osiele Market, and other major markets in the ancient city.

“Many of those women are directly involved in the processing and designing like we do here,” she says, grinning. “But you may not know until you see them ‘get dirty’ inside coloured water here.”

From the sale of Adire, Jumoke told PREMIUM TIMES she has used the proceeds to support her family since her husband lost her job at the height of the Covid-19 crisis.

“Adire making is a good business, and depending on how much patronage we get, the proceeds could run into tens of thousands of naira monthly,” she says.

From a modest kiosk in Itoku, Jumoke says she has since expanded her supply chain to other markets in Abeokuta and beyond. She has equally brought in two of her cousins as aides, including three students of the local Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, Abeokuta.

Boosting Earnings

Nigeria relies on oil and gas for more than 80 per cent of its foreign exchange. Experts have argued that the country can boost its forex earnings by diversifying its revenue base to hedge the economy against the instability of the oil market.

The women producing Adire are not only creating a livelihood for themselves and their families, but are helping in their own way to boost Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings as their products are patronised well beyond Nigeria’s shores.

Adire is quite popular across West Africa. In Nigeria, its production is common among the Egba women entrepreneurs in the South-western part of the country.

Historically, export of the fabric was tied to the formation of Adire makers associations in different parts of Yorubaland, stemming from the complex problem they experienced in Abeokuta in the 1920s.ADVERTISEMENT

According to Bukola Oyeniyi, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Department of Political Studies and Governance, University of Free State, South Africa, attempts at solving these problems brought about two important developments: the introduction of new methods to Adire production, and the influx of many people into the business.

On account of these developments, patronage dropped, thus destroying the industry. Exports fell from £500,000 before 1928 to £150,000 by the mid-1930s, according to records from the National Archive, Ibadan.

In the years that followed, Adire cloth production and export became intertwined with that of cocoa production in Nigeria and Ghana. Again, when cocoa prices plummeted in 1937, the inability of farmers to continue to purchase Adire led to the decline of the industry.

In recent years, there have been conscious efforts to encourage export and spread the local fabrics to different parts of Africa and beyond.

Various styles of the fabric have been exported to markets in the United States, United Kingdom, Asia, and international airports around the world where Adire is sold at premium prices.

Adire fabrics are equally well sold at tourist centres, where merchants buy local materials at higher prices.

In Abeokuta, Iyabo Sodipe, an Adire trader, told PREMIUM TIMES that she exports the fabric to Ghana, Mali, and Ivory Coast, from where she makes as much as $1,215 annually.

“With better incentives and government support, we can do better and export Adire to many parts of Africa and the world and earn good foreign exchange,” she said.

Sayo Jacob, an Osogbo-based trader, said she told nearly $500 worth of Adire in 2019, but could not do much in 2020 due to the pandemic.

Traders, however, complain about the difficulty of exporting the designs, blaming bureaucracy and cost.

Adire

Adire is a Yoruba word that colloquially means “tie and dye”. It’s a material designed with wax-resist methods, that produces patterned creative designs in a dazzling array of tints and hues.

PREMIUM TIMES gathered from women in Itoku that the first female Adire merchant in Abeokuta was Jojolola Soetan, who died in 1932. Since her death, the practice has become a major part of entrepreneurial life among Egba women.

Over the years, the value-chain has been extended to create jobs for a number of women such as the dyer, known as Alaro, and the decorator, known as Aladire, among others.

Adire comes in various forms such as Adire Oniko, Adire Eleko, Adire Alabere and Adire Batani, all with variegated designs and creative patterns.

The Adire Oniko is made out of cotton and indigo dye while the traditional Adire Eleko refers to designs created by the application of starch paste made from cassava flour. This starch resists the dye from penetrating through the cloth.

The starch paste is applied with a brush or feather on the surface of the fabric or through a stencil that has been cut into a design. It is often left to dry under the sun before it is immersed in a dye solution.

As the name implies, Adire Alabere refers to “adire with the needle,” a style of indigo textiles crafted with complex designs of symbols with patterned effect created by stitching the fabric by hand before submerging the textile in indigo dye.

Adire Batani on its part is designed with the aid of zinc stencils and the application of resistant starch.

Ms Bolatito told this reporter that it takes roughly three to four days to complete a yard, with patterns created with no focal point of interest.

She added that irrespective of the pattern of design, Adire making is a money-spinner from which numerous Egba women and other small-scale entrepreneurs earn huge cash.

The value-chain also accommodates young artisans and undergraduates of higher institutions within the Abeokuta metropolis, she said.

SMEs Value-chain

Komolafe Christianah, 23, is a Higher National Diploma (HND) 1 student of the Moshood Abiola Polytechnic, Ojere, where she is studying Accountancy. But she has no plan to look for a job upon graduation.

“Once I graduate, I will go into the full-time business of Adire,” she told PREMIUM TIMES in a chat at her residence in the Oluwo area of the capital city.

She explained that she is on the verge of renting a stall around the Adigbe area of Abeokuta, to aid her supply and sales of Adire fabrics.

“It’s a business I started way back with my mum, immediately after my secondary school education, so I understand it quite well.

“Adire making has huge potential and market, and the future is very promising.”

As a student of MAPOLY, Miss Komolafe said vshe is able to make better sales by marketing to her coursemates and other friends from schools outside Abeokuta.

Like Christianah, Titus Ayobami is another student who is into the supply of Adire clothing, but he is quite new on the job. A 200-level student of the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ayobami said he focuses on markets outside of Abeokuta, especially Lagos, where designers are beginning to make creative designs with Adire fabrics.

“I started supplying Adire material last year during the pandemic, as I had very little to do to make extra cash,” he said in a chat on FUNAAB main campus along Alabata Road in Abeokuta.

“What I have studied and realised is that Adire will go places and it will get to the international market in a short while. But those of us already in the business now would perhaps enjoy the benefits more.”

When asked about his experience in a business largely regarded as female-dominated, he explained that there isn’t any challenge, especially for those on the supply end of the value-chain.

“People always think it is a female-only venture but it is not, although there are more women in the value-chain,” he quipped.

Apart from the women who design the patterns, and students of higher institutions who serve mostly on the supply chain, found that there are numerous others who work in the production and design processes.

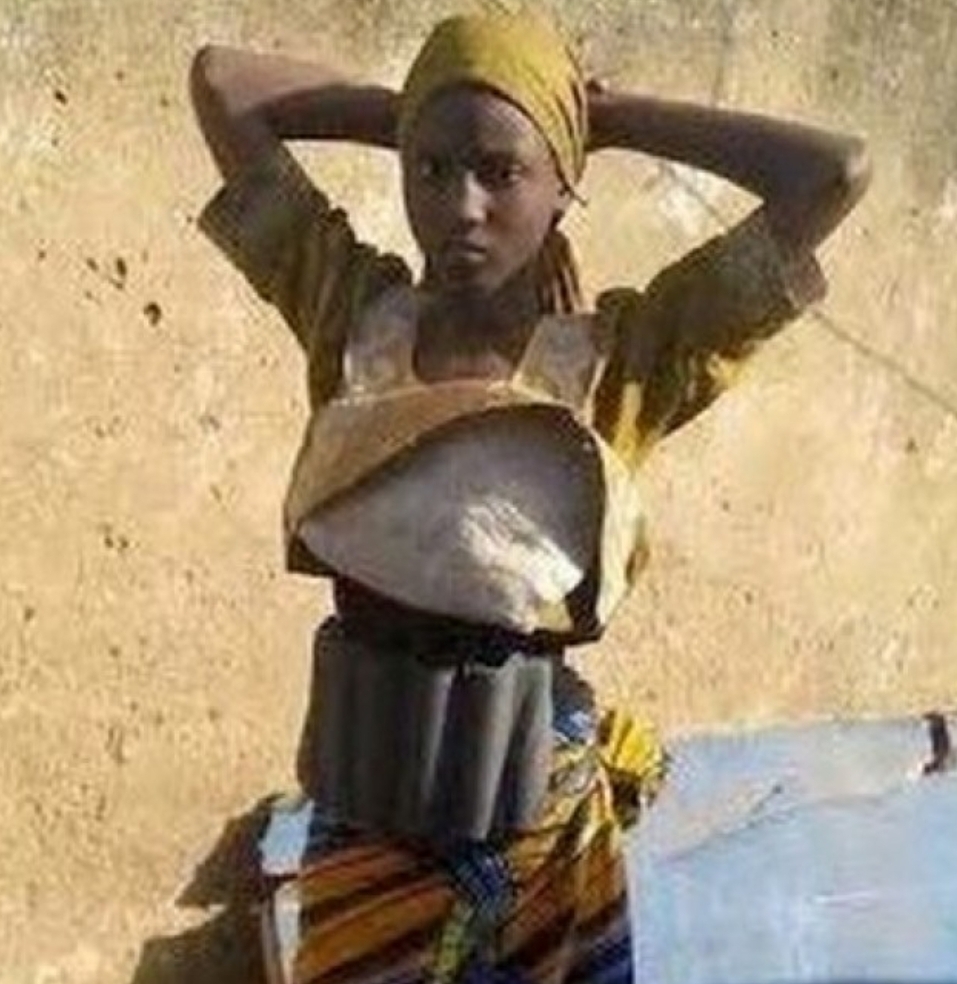

Textile Beaters

Before Adire fabric can be folded for onward supply to buyers, there are textile beaters who beat fabrics for various textile designers, using a wooden mallet and trunk.

34-year-old Ali Ali, originally from Mali, told PREMIUM TIMES at the Itoku cottage that he helps with the beating process.

“We must beat the fabric to straighten it and make it foldable before it can be packaged for sales,” he said.

“If we don’t beat it, the fabric would be rough and difficult to fold into fine patterns.”

Mr Ali and his brother said that they beat an average of 20 to 50 pieces of fabrics daily, depending on the production limit.

“We earn between N30 and N50 per fabric, depending on the clients,” he explains in a smattering of pidgin English.

Despite coming from far away Mali, Mr Ali says he feels at home in Abeokuta because of the ease that comes with his job, from which he earns an average of N80,000 monthly.

In recent years, electronic iron has come to replace the beating process in the Adire value-chain and some of the women entrepreneurs often opt for the ironing process.

Kareem Mudasiru, one of those who iron Adire clothes at a small cottage in Asero, told PREMIUM TIMES that people still prefer the traditional beating process because of the cost and safety.

“I and my colleagues make our money from ironing too but many would rather go for the old beating process,” he sayd

At the Itoku cottage, a number of young apprentices invested in learning the craft and establishing themselves in years to come expressed optimism about the business.

Adeola Joseph, a young school leaving certificate holder, told PREMIUM TIMES she had read so much about the export potential of Adire and the efforts of the Ogun State government to situate it at the centre of its digital economy.

“I am convinced that there is a future in Adire making and I am ready to dedicate myself to it,” she said.

“By the time we begin to export quite well, Adire will become a money spinner for entrepreneurs in Ogun state and Nigeria as a whole. That’s why government must invest in modern technology that will aid operations.”

Challenges

Ms Bolatito said their biggest headache as women entrepreneurs is access to financial support to enable them to expand their businesses and acquire sophisticated equipment that would aid their operations.

“We also need local patronage among Nigerians,” she said, “because our people must appreciate the local fabric before we can make good sales here and outside Nigeria.”

Mrs Sodipe, a trader at the Kampala Market, said the government should work more on building the capacity of the local women through training. She also suggested that government can improve local demand for women entrepreneurs through public sensitization and promotion of local content ideas in government circles.

“They can as well help encourage export, so we can promote our culture across the world while building the economy and creating jobs along the way,” she said.

Despite its huge potential, the development and export of Adire has been plagued by similar concerns militating against the growth of the larger textile ecosystem in Nigeria.

In May 2017, then Acting President Yemi Osinbajo signed an Executive Order which focused on promoting made-in-Nigeria products in public procurements. The Executive Order, titled ‘Support for Local Contents in Public Procurement by the Federal Government’ (LCEO), was premised on the goal of weaning the economy off over-dependence on oil revenues.

But events over the years have shown that the order has been adhered to largely in the breach, as Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) of government still import their uniforms from abroad, even in cases where there is local capacity for production. This is worsened by the heavy dependence on used clothing among many Nigerians.

In 2019, Nigeria placed a restriction on the sale of foreign exchange to importers of textiles and other clothing materials in a bid to protect the textile, cotton and garment industry, and boost employment opportunities.

In 2020, however, details from the National Bureau of Statistics showed that Nigeria’s import figures on textile and textile articles rose to N330 billion, but the nation exported N5.05 billion worth of textile goods as of the third quarter of the year.

Analysts opine that efforts must be deliberately targeted at making policies work for the growth of the textile industry.

A Silver Lining for Adire?

In November 2020, the Ogun State government flagged off the Adire Digital Market at the June 12 Cultural Centre, Kuto, Abeokuta. Speaking at the event, Governor Dapo Abiodun advocated the promotion of Nigeria’s indigenous fabrics to the world, adding that Adire fabrics could be adopted as national wear for athletes during sporting activities.

Mr Abiodun added that the state would be adopting the local fabrics as part of the school uniform for public primary and secondary schools in the state.

He added that plans had reached an advanced stage to make Adire an important aspect of everyday life, as all top government functionaries in the State now wear Adire on Fridays.

Mr Abiodun had in 2020 urged Nigeria’s foreign missions to adopt the Adire fabric as a cultural symbol that will further project Nigeria’s rich culture to the outside world.

Adams Oluwaseyi, a policy analyst, said that beyond beautiful rhetoric, governments at both levels must work on actionable plans to ensure that export of Adire clothing is at the heart of economic policies.

According to him, the export terrain is very complex and near-impossible to navigate for individual entrepreneurs, especially in the absence of government’s intervention that could aid regulatory standards.

In her conversation with this newspaper, Jumoke says that the only ‘export’ experience she had was when she sent five pieces of Adire fabrics to some clients through her cousin who was travelling to the United States in 2018. She admitted that she got a far better bargain, and made more profit.

“But that’s not export, per se, because my cousin simply travelled with them as though they were her own used fabrics,” she said.

A website, AdireOgun, has been launched to promote Adire to a global audience. Mr Adams said it is the right step in the right direction, but advised that more needs to be done to ensure maximum impact.

“We look forward to a more robust export opportunity and strategy supported by the government. It will help diversify our revenue base, create more jobs, boost the economy in Ogun and help Nigeria earn Foreign exchange.

(Premium times)