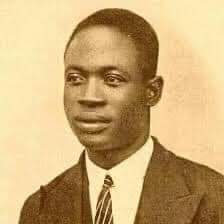

Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), M.S. in Educ. 1943, M.A. 1944, was born in Africa’s Gold Coast (now Ghana). As a young man, he was a school teacher before leaving his homeland to further his education in American universities. He later traveled to England where he worked for the decolonization of Africa and in the Pan-African movement before returning to Africa to lead his country’s independence movement. After the 1957 British withdrawal from his country, Nkrumah became Prime Minister and then, in 1960, the first president of the modern nation of Ghana. Despite his early studies of Marxism, Nkrumah’s political views tended toward socialism rather than to capitalism or communism. During his early years in office, Nkrumah did much to modernize his country. Despite high hopes, however, the difficulties of financing power plants and organizing armies in a poor African country led to corruption, police tactics and wide-spread dissatisfaction. In February 1966, Nkrumah was overthrown while on a state visit to China. He never returned to Ghana but from his exile in Guinea, Nkrumah gained worldwide recognition for his continued efforts on behalf of Pan-African unity.

Kwame Nkrumah arrived in Philadelphia in 1935 to begin undergraduate study at Lincoln University. After completing a bachelor’s degree in Sociology magna cum laude, Lincoln admitted him to its Theological Seminary in 1939 for an additional degree in Sacred Theology. It was at this time, however, that Nkrumah began concurrent enrollment at the University of Pennsylvania in the hopes of acquiring multiple degrees simultaneously. Supporting himself through a precarious combination of scholarships and seasonal work in the segregated shipyards of Philadelphia, Nkrumah regularly visited Harlem and Washington to speak on anti-imperial themes in churches, on street corners, at political rallies, and in classrooms. In so doing, he managed to meet such prominent intellectuals of the African diaspora as C.L.R. James, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Marcus Garvey. As he later recalled in his autobiography, “Life would have been so much easier if I could have devoted all my time to study. As things were, however, I was always in need of money.”

603 N. 39th Street, is Nkrumah’s residence while attending the University of Pennsylvania.

After receiving his Master’s degree from Penn’s Graduate School of Education in 1941, Nkrumah began another program of study with the Department of Philosophy on a University Scholarship. His advisor Glen Morrow noted that he satisfied the requirements for a Master’s degree in Philosophy in 1943, and by 1944 it appears that he had passed his preliminary exams for a doctorate. He then began working as an “instructor-informant” for Zelig Harris in a new African Studies graduate group, and in 1945 he left the United States for London and Manchester. He finally returned to the Gold Coast in 1947.

We have some more tangible traces of his intellectual life during this time. While his theses in education and philosophy have unfortunately been lost by the University, he did publish two articles in Penn’s Educational Outlook that give some indication of the extent to which he was already developing the Pan-Africanist challenge to colonialism that we now associate with him.

His first article was in 1941, when he was most probably completing his education degree, and it is not surprisingly titled “Primitive Education in West Africa.” In it, Nkrumah suggested that the traditional educational institutions of Africa conformed to the prevailing educational theories of the mid-20th century. He notes that

… the education of a child is largely a process of acquiring, in the first place, conditioned reflexes, and then, the more permanent associations and systems of conditioned reflexes that we call habits. The leaders of primitive West Africa, for a long time, consciously or unconsciously, have been aware of this psychological fact.

He also proposes that African teachers rightly understood the importance of early childhood in the learning process, and thus began education at a very young age, and he pointedly observes that the colonial-era need for African orphanages was a consequence of the destruction of traditional educational institutions, which unlike the European model, integrated “infant welfare” and schooling.

In his conclusion: West African education “gave efficient preparation for the activities of life and so it fulfilled its purpose,” an implicit suggestion that it was the equal of—and in some ways superior to—its colonial counterparts.

His other article, which appeared in 1943, is a more explicit connection of colonialism and the struggle over African educational institutions.

In “Education and Nationalism in Africa,” Nkrumah presents a focused discussion of the tensions between European colonial rule, education, and national emancipation. After referring his reader to the previous discussion of traditional education in West Africa, Nkrumah presents a short history of European mission schools in Africa, which he suggests were the primary educational institutions of colonial Africa. After noting that their Eurocentric curricula carefully excluded African religion, culture, and history, he observed that

…under such a system of

education the youth of Africa is not prepared to meet any definite situations of the changing community except those of the clerical activities and occupations for foreign commercial and mercantile concerns.

In his view,

…any educational program which fails to furnish criteria for the judgment of social, political, economic, and technical progress of the people it purports to serve has completely failed in its purpose, and has become an educational fraud.

Pointing to the hypocrisy of a civilizing educational mission that permanently delayed graduation, the moment when Europeans would deem Africans capable of managing their own affairs, Nkrumah ultimately concluded that “Higher education is incompatible with colonial status.”

Two dissertation-length manuscripts from this period of Nkrumah’s life can now be found in the Ghana National Archives, one entitled “The History and Philosophy of Imperialism with Special Reference to Colonial Problems,” and another, “Mind and Thought in Primitive Society: a study in Ethno-Philosophy with Special Reference to the Akan Peoples of the Gold Coast, West Africa.”